Backbench to the Future - How Modern Canadian Politics Resembles British Political History

As anyone who knows me well will tell you, I’m mildly obsessed with Canada. Ever since visiting in 2023, I’ve been continually hyper-fixated on its culture, history, and, most importantly, its politics. None of this has been helped by one of my favourite YouTubers, J.J. McCullough. whose videos provide an easy-to-grasp insight into Canadian life and politics. While I may not agree with him politically, he has certainly helped me develop a love for Canada. This love even extended to Canadian postboxes, which I took several photos of on my visit, as he had mentioned them in a video. Please see a wonderful example below. I'm now so obsessed with the country that a Canadian flag of one kind or another has been hung on my bedroom wall for the last two years (It’s currently the flag of the Canadian Forces for all of you who are just dying to know).

So, as you can imagine, when former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau resigned earlier this year, my interest was piqued. I was so interested that I even sat and watched his resignation speech live. As I continued to pay close attention to the Liberal Party leadership contest in the following week and consumed a lot of Canadian political content, I couldn’t help but notice some similarities to British politics. This continued right up to the Canadian election in April, where I noticed even more similarities. While this isn’t surprising in any sense, Canada and the UK do share a very similar Westminster system, as shown by King Charles III’s recent visit. What struck me most was that the similarities I was noticing were not just from recent examples in British politics. Instead, lots of the modern developments in Canadian politics reminded me of facts I knew about 19th and 20th-century British political history. So I went on a deep dive and realised that it wasn’t just my mind playing tricks on me. Canadian politics was using conventions, traditions and political norms that are long forgotten in the world of British politics. Therefore, for the second instalment of the Hyperfixation Report, I thought I would detail just two ways in which Canadian politics is reflecting the British politics of yesteryear.

The first example comes from the election of Mark Carney as leader of the Liberal Party, and by extension, Prime Minister of Canada. While Mark Carney’s election follows a similar pattern to UK politics with an incumbent PM resigning to be replaced mid-term by another leading figure, think Liz Truss taking over from Boris Johnson, his election was anything but ordinary. The reason for this was the fact that Carney was not a Member of Parliament and, in fact, had never held an elected office in his life. This meant that when he beat his competitor Chrystia Freeland in a landslide and was sworn into office by the Governor General a few days later, he was Prime Minister without being able to sit in Parliament. What was striking about this result was that there was very little discussion about the matter. It didn’t cause any concern amongst the membership of the Liberal Party, who gave him over 85% of the vote in the leadership contest. Ultimately, Carney was PM for 45 days while not being an MP before he won the Riding of Nepean in April’s Federal Election. While this situation is rare in Canada, it is much more common than one would initially expect. In fact, a similar situation occurred in 1984 with the resignation of Pierre Trudeau, father of Justin Trudeau. Pierre Trudeau was then replaced by John Turner as PM who also did not hold a seat in Parliament and governed without being able to sit in the House of Commons. While similar to Carney, he was not nearly as successful, with the Liberal Party, under his leadership, being defeated in the 1984 election. This made him Canada’s second shortest-serving PM, a fate Carney managed to avoid.

Evidently, then, this is an accepted, albeit rare, feature of Canadian politics. In the UK, the opposite is true. While constitutionally sound, a PM must command the confidence of the House of Commons, which does not require them to be a member of it, it is not politically tenable in our modern political system. I’m sure all of you reading this would find the notion of an unelected person being made PM quite difficult to grasp in the 21st Century. However, this was not always the case. Throughout British political history, there have been examples similar to Mark Carney with our past Prime Ministers either governing outside of Parliament or as an unelected Peer in the House of Lords. The most ‘recent’ example from our political history comes from the premiership of Sir Alec Douglas-Home, who served as UK Prime Minister from 1963-64. Douglas-Home was a Conservative hereditary peer when he was chosen by the Conservative Party to replace Harold Macmillan. Already by 1963, the appointment of a Peer as PM was controversial with the convention that the PM should be from the Commons, having become well established in the British political sphere. As such, Douglas-Home resigned his peerage only a few days after having been appointed PM and announced his intention to fight a by-election in order to enter the Commons. This he duly did and was elected 25 days after having resigned his peerage. This meant that for those 25 days, he was not a member of either House of Parliament, just like Mark Carney. He is the only British PM to have governed as a member of neither House, unlike Canada, which has seen several. To find another example of a PM who was not a member of the House of Commons, you have to go back to 1902 with Lord Salisbury, who, as the name suggests, governed as a member of the House of Lords. This shows very clearly how recent events in Canadian politics are reflecting long-forgotten norms from British political history.

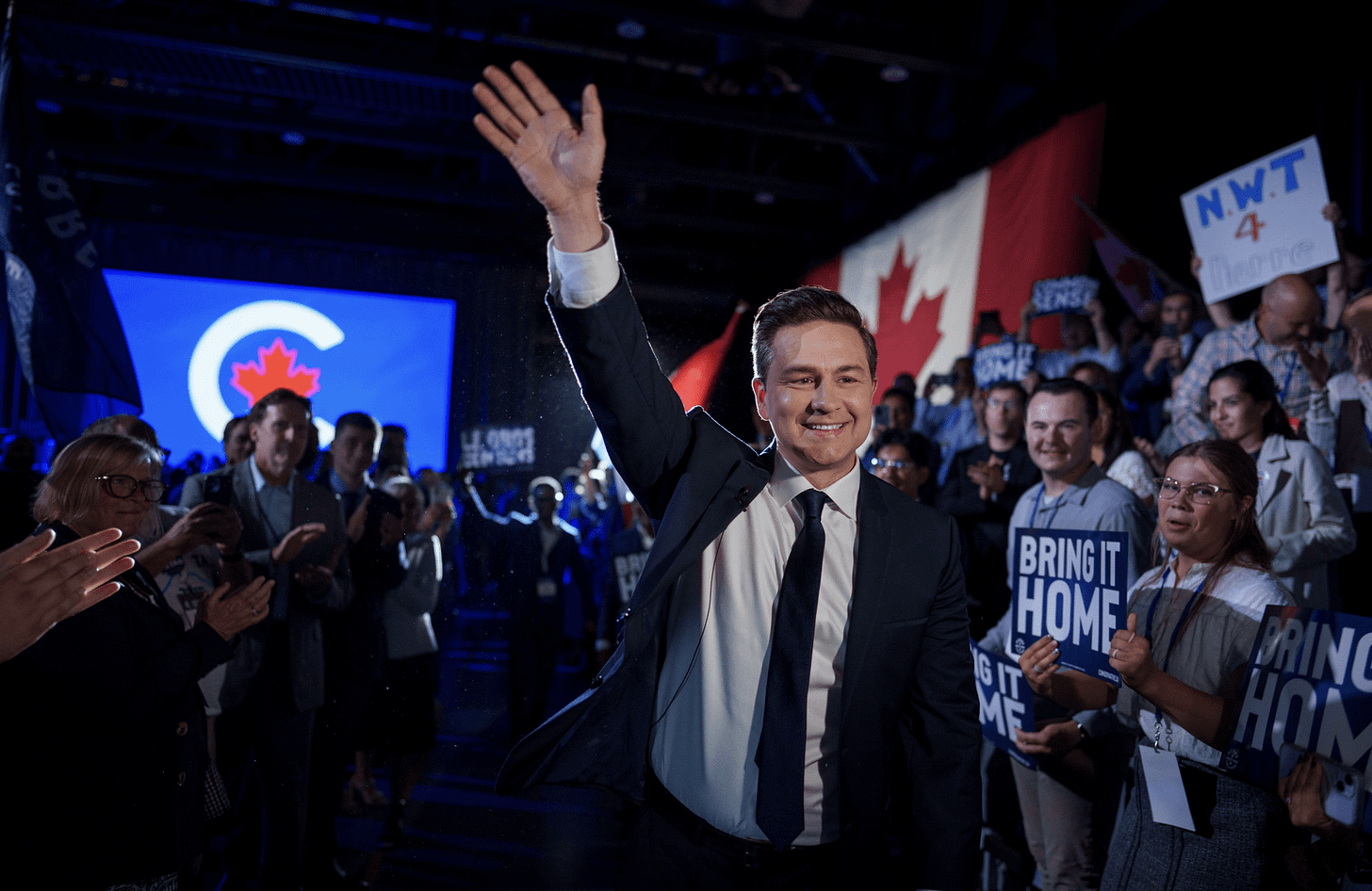

The second example of this phenomenon comes from Mark Carney’s main opponent, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre. For months, Poilievre’s Conservatives had seen significant polling leads in the build-up to the 2025 Federal Election. All of this came crumbling down upon Carney’s election with the Tories trailing in the polls. While the party did manage to increase its vote and seat share in April’s election compared to the 2021 election, the Conservatives ultimately still suffered a defeat. This was vividly illustrated by Poilievre losing his Riding of Carleton to the Liberals. The incumbent leader of a major party losing their seat in an election is often considered an exquisite form of political death in the UK, with very few ever returning from such an event. Just look at the example of Jo Swinson, leader of the Liberal Democrats, who lost her Mid Dunbartonshire seat in the 2019 General Election and resigned as party leader immediately. When was the last time any of you heard of her? How about the Scottish Labour Party leader Jim Murphy, who lost his seat in the Commons to the SNP in 2015? In Canada’s case, however, Poilievre has remained as leader of the Conservative Party with little opposition to him doing so. One Tory MP has even offered to resign his safe seat for Poilievre to return to the Commons, which looks likely to happen. In the meantime, the role of Leader of the Opposition is being filled by former Conservative leader Andrew Scheer until Poilievre can return, which will happen at the earliest in August.

Once again, the idea of a defeated party leader, or notable party figure, returning to the Commons in a by-election is an alien one to modern British readers. While again it is constitutionally sound, it is not particularly politically viable; once you have lost an election in the UK as a party leader, your time is almost always up. Just think of Neil Kinnock, William Hague, Ed Miliband, Rishi Sunak, etc. Additionally, if you have lost your seat as a ‘big beast’, it is highly unlikely you’ll make a return, like Ed Balls, for example. The British system is very brutal in that regard. However, throughout British political history, this was not always the case. Notable figures and party leaders were often booted from the Commons in a general election, only to return months later in a by-election. This includes Winston Churchill, who attempted this feat unsuccessfully in both 1923 and 1924 after having lost his Dundee constituency in the 1922 general election. A more successful example comes from Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister from 1902-1905, who, after having lost his seat in the 1906 General Election, managed to return to Parliament as Leader of the Opposition after winning the February 1906 City of London by-election. Once again, this shows how modern developments in the Canadian political sphere closely resemble the political past of the UK.

While there is a striking resemblance between modern Canadian and historical British politics, these events are still uncommon in Canada and don’t reflect ‘business as usual’ in the Canadian system. However, what they do show is how closely our two countries are in terms of political cultures and conventions, and this highlights an even more important point. While Canadians can look at British political history and see similarities to their current political reality, perhaps we Brits can also view Canadian political history in a similar light. In the 1993 Canadian election, the incumbent PM Kim Campbell led her Progressive Conservative Party to a historic defeat. One of the two major parties in Canadian politics was decimated, down from 169 seats to just 2. This catastrophic result was partially due to the rise of the populist, right-wing Reform Party, sound familiar? In the end, the Reform Party and the Progressive Conservatives merged into the modern Conservative Party of Canada to ‘unite the right’. While not entirely similar to what is occurring in modern British politics, there are clear parallels. Nigel Farage himself has even stated that he has taken inspiration from the Reform Party of Canada. Maybe we should all pay more attention to Canadian political history if we want to understand what our political future in the UK may hold?

- Thomas